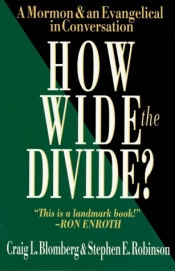

How Wide the Divide (IVP Academic, 1997)

How Wide the Divide (IVP Academic, 1997)

By Craig L. Blomberg and Stephen E. Robinson

Reviewed by Bill McKeever and Eric Johnson

Since the founding of the LDS Church in 1830, both Christians and Mormons have disagreed as to what constitutes correct doctrine. Too often apologists from both sides have criticized from afar, having little personal contact with their “opposition.”

Except for scattered debates, the two sides rarely, if ever, sit down to discuss in an open format to honestly discuss, point-by-point, the differences between these two faiths. However, with the publication of How Wide the Divide? A Mormon & an Evangelical in Conversation (InterVarsity Press, 1997), this has all changed.

How Wide the Divide? is published by a well-known Christian publisher as a dialogue between Stephen E. Robinson, a Brigham Young University professor of ancient scripture, and Craig Blomberg, a professor of New Testament at Denver Seminary. As stated on the back cover, its basic premise is as follows:

“Mormons and Evangelicals don’t often get along very well. They often set about trying to convert one another, considering the faith the other holds as defective in some critical way. Unfortunately, much of what they say about one another simply isn’t true. False stereotypes on both sides prevent genuine communication.”

The book deals with four main issues: 1) scripture; 2) God & deification; 3) Christ and the Trinity; and 4) salvation. In 10-15 pages, the format allows each author to present his viewpoint of these issues along with a rebuttal of the other’s position. It appears that they were given the other writer’s chapters before the book’s publication. Thus, specific points made within the book are referenced and rebutted.

Despite the good intentions of the authors, the book has fundamental problems at its core. Since How Wide the Divide? often clouds essential issues rather than clearly defines them, many innocent Christian laypeople might view the differences between Mormonism and biblical Christianity to be minimal when they really are not. This review is not meant to be exhaustive, by any means, but we feel it is important to express our position with this book.

Introduction: Where should we go to understand the other side?

From the very beginning, Dr. Robinson attempts to show that the “divide” between Mormonism and biblical Christianity is smaller than many Christians make it out to be. In the first paragraph, he gives the story about a group of Christians who threatened to leave an anti-pornography committee when some interested Mormons inquired about joining the group.

This, Robinson lamented, shows that “some Evangelicals oppose Mormons more vehemently than they oppose pornography” (p. 9). Such a conclusion is wrong. Christians who hold the Bible dear want no more to legitimize Mormonism than they want to allow pornography. The refusal to join with Mormons stems more from a desire not to give them credence as a Christian organization; and rightly so.

Robinson lays the blame of misunderstanding at the feet of “extremists” who misinterpret each other’s terminology. He explains: “…much of what separates us is in my opinion false impressions, which are generated by extremists on both sides or are caused by misunderstanding each other’s theological terminology.” Quite the contrary, it is in understanding LDS terminology that one truly understands the LDS position.

Says Robinson,

“Evangelicals and Latter-day Saints share the same moral standards, the same family values, the same old-fashioned standards of personal conduct. We have the same reverence for the sacred. We both interpret the Scriptures literally and believe them to mean what they say…. Most Evangelicals and Latter-day Saints alike would be surprised at the amount of theology we share”(p. 10).

While we may share many of the same moral values as Latter-day Saints, many of those values are also shared by other groups such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Christian Scientists, and Muslims. Are we supposed to accept them into the Christian fold as well? While Robinson speaks of a reverence for the sacred, Christians do not revere the same things Mormons do. For instance, the Bible-believing Christian does not consider the following as “sacred”:

- temples made with human hands;

- protective undergarments known as the garment of the Holy Priesthood;

- the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, or Pearl of Great Price;

- a concept of God that resembles that of corruptible man;

- a created Jesus who is Lucifer’s spirit brother.

These are just a few examples that, instead of being considered sacred in the Christian viewpoint, are false teachings with no basis of truth.

The premise Robinson holds is that Mormonism can best be understood by talking to Mormons like himself. The problem we find is that Robinson walks a very fine line between what he believes to be the true LDS position and official LDS teaching. Instead of quoting LDS leaders to support LDS theology, Robinson provides nothing more than his opinion about what makes up LDS orthodoxy.

This, in our opinion, is the fatal flaw of this book. Instead of hearing what those in authority have to say on these very important issues, we get the opinion of a BYU professor. Despite his “Melchizedek Priesthood,” Robinson has no more authority to speak for his church than do the Mormon missionaries he derides (p. 15). He even makes this clear when he writes,

“I do not speak in this volume for the LDS Church, only for myself, but I think I qualify as the world’s authority on what I believe, and I consider myself a reasonably devout and well-informed Latter-day Saint” (p. 14).

We think that this disclaimer offers the biggest clue as to what the reader may find within the covers of How Wide the Divide?

Robinson claims,

“In the short run, LDS orthodoxy is defined by the Standard Works of the Church (Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price) as interpreted by the General Authorities of the Church – the current apostles and prophets” (p. 15).

The key to what he is saying is found in the phrase “current apostles and prophets.” Robinson, like many LDS, cringes whenever an early LDS leader is quoted. Robinson chooses to distance himself from the brash and blunt rhetoric of early Mormonism.

It appears that he would much rather cling to the ambiguous and politically correct statements coming out of modern Salt Lake City. We find that it is getting extremely hard to find a leader who will boldly proclaim the intricate doctrines of his faith. Apparently the days of Bruce McConkie, Joseph Fielding Smith, and Spencer Kimball are a thing of the past.

Using a blanket approach to lump Mormonism’s detractors together, Robinson says that we who belong to the countercult ministry apparently are

“fundamentalist anti-Mormons who incessantly attack us, and (are) dishonest because these so-called anticultists always insist the LDS believe things we do not in fact believe” (emphasis his). He also writes: “I might add that the worst way for Evangelicals to learn about Latter-day Saints is to ask other non-Mormons or to read non-Mormon literature about the Saints” (p. 14).

We find it reprehensible that Robinson would say ministries like ours are dishonest and are always (remember, this was his emphasis) insisting Mormons believe things they do not believe. While we can’t speak for everyone, we have been commended numerous times by Mormons for our grasp of LDS doctrine. Anyone who has read our material knows the pains we take to document our writings about the LDS faith. We have neither the time nor the imagination to make up such things.

Contrary to this unfair accusation, we believe that Mormonism Research Ministry and the vast majority of the Christian ministries with outreaches to the LDS are guilty of nothing more than explaining Mormonism through the voice of important LDS leaders.

We should note that the writers at this ministry try not to reference anyone less than an LDS Seventy, with the majority of our quotes coming from the church’s apostles and prophets. We would never insinuate that an off-the-cuff remark from a Mormon missionary, bishop, or BYU professor is authoritative unless a general authority and/or the LDS standard works supported it.

Where, then, should a Christian who wants to understand Mormonism go? One would think that the many missionaries sent out by the LDS Church could provide answers. However, Robinson isn’t so sure this is a good idea. He describes these representatives of his church as “almost literally babes in the woods, and quite often, particularly where the Mormon Church is strong, the LDS missionaries might be among the least knowledgeable members in a congregation” (p. 15).

Certainly this speaks volumes as to the credibility of such a program. Imagine a church that sends out tens of thousands of missionaries who are long on zeal but short on knowledge! One can only imagine what kind of credible information those who are investigating the LDS Church are getting under the tutelage of such “babes in the woods.”

Apparently Robinson also questions the wisdom and capability of those in authority over his church. On page 45 in his book Believing Christ, Robinson related an incident when he asked his students about whether or not keeping the commandments were necessary to gain entrance into the celestial kingdom. Robinson personally does not believe this is a requirement, but when his students answered affirmatively to his query, he conceded that the reason they believe this was because “they have heard Church leaders and teachers tell them so all of their lives.”

While we have a great admiration for Blomberg’s contribution to the Christian cause, we personally feel his inexperience in dealing with Mormons on a more personal level made him prey to Robinson. He makes the mistake of assuming too much when it comes to Robinson’s defenses. Instead of challenging Robinson to defend the comments made by those in LDS authority, he too often allows Robinson’s statements to stand as LDS orthodoxy.

It would have been nice if Blomberg had come to the defense of those who have dedicated their lives to defending the faith against heresies such as Mormonism. Instead, Blomberg writes:

“Evangelical writers, however well-intentioned, are not likely to know nearly as much about Mormonism as LDS writers, unless they have lived and ministered for years in predominantly Mormon parts of the country” (p. 22).

If this is truly the case, what qualifications could Blomberg himself bring to the table to be able to critique Mormonism? How would he know if he were being told the truth as it relates to Mormonism? Would he be able to correctly discern between Mormon doctrine and Robinson’s personal opinions?

Scripture

Blomberg has a good grasp on the authority of the Bible and textual criticism, which is the process of how we got our Bible. Concerning the closing of the canon, he writes:

“In principle, unless we want to fall back on the Catholic position that the church creates the canon and is ultimately responsible for giving its imprimatur to the books we will accept, we must allow for the possibility that if some other ancient book could meet all the qualifications that commended the other sixty-six books that all Christians agree belong in the canon, then it too might be added” (p. 39).

Personally we do not have a problem in a theoretical sense with what might seem to be a troublesome position. However, as Blomberg points out, such a hypothetical book must agree with the theology and doctrines as already presented in the Bible we have today (p. 41). This is one of the primary reasons we as Christians cannot accept the unique teachings of the LDS Church; that is, they do contradict what God has already revealed.

Blomberg gives five important concerns he has about other LDS scriptures, which are the Book of Mormon, Doctrines and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price. He is uneasy about the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) of the Bible, and he raises significant questions about the Book of Abraham. For Blomberg, the Book of Mormon is not an ancient book, but instead he feels the evidence points to its being a 19th century story.

Robinson’s defense of the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) hardly settles the issue. On page 64 he writes, “Certainly the existence of a JST variant reading for a passage ought not to imply that the KJV is incorrect, since the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants sometimes agree with the KJV rather than the JST.”

Robinson’s conclusion is certainly out of harmony with those who held a much higher position of authority than he. For instance, LDS Apostle Bruce McConkie said God commanded Smith to retranslate the Bible since it “does not accurately record or perfectly preserve the words, thoughts and intents of the original inspired authors.” McConkie said Smith “corrected, revised, altered, added to, and deleted from the King James Version of the Bible to form what is now commonly referred to as the Inspired Version of the Bible” (Mormon Doctrine, p.383). On more than one occasion, tenth LDS President Joseph Fielding Smith said the JST “corrected” errors in the King James text.

One area not adequately answered by Blomberg is Robinson’s emphasis on Mormonism’s eighth Article of Faith, which states that the Bible is true “only as far as it is translated correctly.” Robinson says that Mormons agree with Blomberg’s opinion that there are transmission errors only. This is only a cautionary warning, Robinson insists, and does not mean Mormons don’t otherwise fully trust the Bible.

However, having had the opportunity to speak with literally hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Latter-day Saints, we find that such a position to be quite rare among the general Mormon population. When challenged to defend their position from the Bible, most Mormons choose to discredit what it says in favor of what they call “modern-day revelation.” Certainly to hear a Latter-day Saint disparage the Bible when confronted with its teachings is anything but a rarity.

Robinson makes another point on page 59, saying “what God has said to apostles and prophets in the past is always secondary to what God is saying directly to his apostles and prophets now.” According to Robinson, just as the teachings of Peter and Paul went against the Old Testament norm, so too should modern prophets and current revelation be believed even when it sounds like strange doctrine. However, what Peter and Paul taught merely fulfilled, not contradicted, the teachings as found in the Old Testament and expounded upon by Jesus.

This would have been a good opportunity to show how Mormon doctrine has shifted and contradicted itself over the last two centuries. For instance, it had been taught in the LDS Church that polygamy was to never be abolished.

However, the Manifesto, as supposedly given by God in 1890, reversed this steadfast doctrine. In a similar way, the doctrine of blacks holding the priesthood was overturned in 1978. This, too, contradicted the teachings of the church’s first 140 years, whose leaders declared that this was to never occur until every white male had already been given the opportunity to receive it.

On page 60, Robinson writes: “Yes, Latter-day Saints believe things that Evangelicals do not, but the huge amount of doctrinal and scriptural overlap and agreement between us is much greater than the disagreement.” While the terminology may seem similar, the differences in meanings are immense.

Then, on page 61, Robinson adds: “…it is not internally consistent with the Saints’ own theology to refer to modern Christians as ‘apostates’—though many still do it. This is rhetoric left over from the nineteenth century. Informed Latter-day Saints do not argue that historic Christianity lost all truth or became completely corrupt” (emphasis his).

He also says,

“But the LDS do not believe [that the universal apostasy of the church meant there were no true Christians]. While the ‘fullness’ of the gospel was not available during that time, there was a knowledge of Christ, there was some light left in the world…” (p. 72).

Calling modern Christians “apostate” is certainly a title given to them by LDS leaders in this modern age. Expressions like apostate Christians, apostate Christendom, and apostate Christianity are found in numerous modern LDS writings. How Robinson can say this is not “internally consistent” with LDS theology undermines the authority of those leaders who used such expressions.

Robinson insists that when the Book of Mormon speaks of the “great and abominable church,” it is not referencing “any specific denomination or even group of denominations.” Instead he interprets this as being anyone—whether LDS or non-LDS—who fights against the Lamb of God. The problem is many LDS leaders have equated criticizing the LDS Church with fighting against God, or in this case, the Lamb of God. This would certainly include many of he Christian denominations that still see Mormonism as a non-Christian religion.

Perhaps the authors could have explained how the doctrines of Mormonism and biblical Christianity moved closer together over the last two centuries. And how has 1 Nephi 14:10, which teaches that all churches outside the LDS Church belong to the “church of the devil,” changed since the Book of Mormon was first printed in 1830? McConkie insisted that when the Book of Mormon speaks of the church of the devil that this includes “modern Christianity in all its parts” (The Millennial Messiah, pp. 54-55).

On page 73 Dr. Robinson makes this amazing statement: “I personally have many, many non-LDS friends, some of whom dislike my faith very much, with whom I fully expect to sit down along with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the Kingdom of heaven.”

On page 153, Robinson states that he feels a “very large percentage” of those who will enter the celestial kingdom will be “Evangelicals.” Given the fact that even LDS leaders don’t give much hope for many Latter-day Saints to make it into the celestial kingdom, what makes Robinson draw this conclusion? To our knowledge, the verses he cites have always been interpreted to refer to faithful Latter-day Saints, not non-LDS “Gentiles.” While such a loophole seems to apply to those who have never heard the LDS “gospel,” those who reject Mormonism during their mortality will never have the chance of obtaining celestial glory in the next life. Does Robinson truly not know this?

Robinson’s analogy also makes us wonder what happened to the LDS concept of a total apostasy. It must be pointed out that Mormonism was founded on the premise of Christianity’s complete and total apostasy. Without this there would have been no need of a restoration of the Christian church. One would assume a “true Christian” is one who has obtained “true salvation.” If that were possible before 1830, then what purpose does the LDS Church serve?

It also appears obvious that Robinson wishes he could censor the teachings of past leaders as they are found in the Journal of Discourses. In our discussions with Latter-day Saints, we find it consistent that whenever a Mormon argues that this 26-volume set should not be considered as always being factual, it is because he does not agree with a particular teaching in question. At the same time Robinson dares not accuse those with whom he may disagree of speaking irresponsibly.

We wish Dr. Robinson and other Mormons who do not like what the leaders quoted in the Journal of Discourses have to say would be forthright enough to admit these men were teaching error. As far as we know, everyone quoted in the Journal of Discourses was much higher on the authority ladder than Robinson.

Who is he to say these men were not speaking truth? If they were speaking truth, why doesn’t Robinson agree with them? If Robinson really believes all doctrine can be found in the standard works, then why are living prophets needed in the first place?

Robinson says, “During my lifetime, and especially during the last decade, the instructions to members have consistently run along these lines: Never mind the Journal of Discourses; return to the Scriptures; stick to the Standard Works” (p. 68). That may suffice for some Mormons, but it seems to negate the purpose for a living prophet. If the general authorities are supposed to explain what the standard works are saying, why not let them speak? Many of the sermons recorded in the Journal of Discourses are doing just that as they provide the mindset of early LDS leaders and what they felt was truth.

These include the nature of God and the requirements for salvation. Those Mormons who do not like what they taught should reconsider their membership instead of criticizing Christians for quoting them. Furthermore, if Robinson is being truthful in saying that church instructions to the membership has been to “never mind” the Journal of Discourses, then why do LDS leaders continually quote from this resource in their lectures and church manuals?

Robinson insists that “Latter-day Saints do not understand why Evangelicals seem to mistrust the direct guidance of the Holy Spirit in interpreting Scripture” (p. 73). It is not so much that we “mistrust the direct guidance of the Holy Spirit.” The problem we have is when Mormons insist that the Holy Spirit taught them something that clearly contradicts what God has already revealed in the Bible. While some Mormons are fairly good at following the rules of hermeneutics when it comes to their unique books, they often break those rules when it comes to interpreting the Bible.

The average Mormon wants the Evangelical Christian to “pray” about the Book of Mormon and look for a certain feeling that assures him or her that Mormonism is true. God has already given His directions regarding things such as religious books. Suffice it to say that the Christian does not deny the efficacy of prayer, but the Bible commands the believer to test all things. (See 1 John 4:1; Jude 3; Galatians 1:8-9; among others.) Praying over such matters is an abuse of prayer and sacrilegious at best. This is an issue that is not fully dealt with according to the Christian perspective, but since Robinson introduces it, perhaps it should have been.

Interestingly enough, the authors conclude the chapter with this: “We find on the topic of Scripture more agreement between us than we had expected to find” (p. 75). In light of the information presented here, we can’t agree.

God & Deification

If there is a doctrine that the Mormon and Christian would certainly part paths, the idea of God and men becoming Gods would be such a doctrine. Blomberg makes a good case for the doctrine of one God, explaining the anthropomorphic language used by many Mormons as examples of how men may become gods. In fact, this chapter could very well be his strongest as he answers many of Robinson’s arguments for the existence of more than one God.

A great point made by Blomberg is quoted here:

“The common Evangelical perception, and we hope we are mistaken, is that Mormons talk a whole lot more about the process of human exaltation than about the eternal worship of a one-of-a-kind God. Their focus seems to be human-centered rather than God centered” (p. 107).

It seems that Mormons too often appear to be more concerned with their potential godhood than they are about worshipping an almighty God. Many Mormons seem to have a misconception that heaven will consist of playing harps and sitting on clouds for eternity. This leads them to mock the idea that sex (or “eternal increase”) and a physical family will not continue into eternity.

Robinson begins his defense by quoting numerous passages from the standard works that describe his God as omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, infinite, eternal and unchangeable. In doing so, he claims that “it just won’t do to claim Mormons believe in a limited God, a finite God, a changeable God, a God who is not from everlasting to everlasting, or who is not omniscient, omnipotent and omnipresent” (p. 78).

The problem is, the words Mormons use to describe their God do not match the descriptions given in the Bible. Robinson fails to point out that on numerous occasions, his leaders are the ones who make the distinction between their God and the God worshipped by mainstream Christianity. If they have admitted there is a difference, why doesn’t Robinson?

Robinson appears to downplay the LDS teaching that men can become Gods by claiming,

“Those who are exalted by his grace will always be ‘gods’ (always with a small g, even in the Doctrine and Covenants) by grace, by an extension of his power, and will always be subordinate to the Godhead. In the Greek philosophical sense – and in the ‘orthodox’ theological sense – such contingent beings would not even rightly be called ‘gods,’ since they never become the ‘ground of all being’ and are ever subordinate to their Father” (p. 86).

First of all, numerous LDS leaders have used a capital G when referring the idea of men attaining godhood. We can appreciate Spencer Kimball’s candidness on this subject when he unhesitatingly said, “To this end God created man to live in mortality and endowed him with the potential to perpetrate the race, to subdue the earth, to perfect himself and to become God [notice the capital G], omniscient and omnipotent” (The Miracle of Forgiveness, p. 2). It seems obvious that if a being has the attributes of God, that being is a God. Robinson’s argument is misleading.

Christians would, and do, have a problem with calling anything subordinate to another as “God.” For this reason Christians have a difficult time accepting Robinson’s God. According to LDS theology, men are able to become Gods because that is the pattern that has been followed since eternity. James Talmage taught,

“We believe in a God who is Himself progressive, whose majesty is intelligence; whose perfection consists in eternal advancement – a Being who has attained His exalted state by a path which now His children are permitted to follow, whose glory it is their heritage to share” (Article of Faith, p. 430).

If, as Robinson correctly notes, all “gods” will forever be subordinate to the Father, then consistency demands that Elohim will always be subordinate to the God(s) who preceded him. Joseph Smith taught,

“There are Lords many, and Gods many, for they are called Gods to whom the word of God comes, and the word of God comes to all these kings and priests. But to our branch of the kingdom there is but one God, to whom we all owe the most perfect submission and loyalty; yet our God is just as subject to still higher intelligences, as we should be to him.” (The Words of Joseph Smith, August 13, 1843, p. 299).

This cannot be the omnipotent God the Bible.

Christ & the Trinity

Blomberg points out some of the misperceptions of the Trinity held by many Mormons and even some Christians. In this context he states, “Not much depends on whether we can correctly articulate our beliefs in every detail, but everything depends on whether historic Christian beliefs are in fact true“ (p. 119, emphasis his).

In this chapter Blomberg expresses grave concerns regarding the LDS perception of the Godhead and how that affects their belief in the nature of Jesus. He criticizes the Mormons who read too much into the phrase “only begotten,” which they use to support their view that God created Jesus.

In this arena Robinson does some scriptural gymnastics, not an uncommon LDS defense. He attempts to use passages from the Book of Mormon that speak of the oneness of the Godhead and states, “That Father, Son and Holy Spirit are one God is, as Blomberg has pointed out, a paramount doctrine of the Book of Mormon.”

However, like most Mormons, Robinson concludes that such passages do not refer to an “ontological oneness of being (that is a creedal rather than a biblical affirmation), but a oneness of mind, purpose, power, and intent” (p. 129). Whereas Robinson refers to Amulek’s conversation with Zeezrom in Alma 11:26ff (p. 129), he does not explain how such passages can be understood only to mean one in purpose. Clearly Amulek declares there is only one true and living God, not three, or even millions, as Mormons have insisted.

Robinson states on page 132 that “it would horrify the Saints to hear talk of polytheism.” By definition, Mormonism does fall under the category of being a polytheistic religion since polytheism basically means to believe in, or worship, many Gods. Since Mormons insist they worship only one of those Gods (Elohim), it would probably be more accurate to say Mormons are henotheistic. Henotheism describes those who worship one God while believing in the existence of many gods. Both polytheism and henotheism are unbiblical.

Robinson claims Jesus was begotten by some “unspecified manner” and insists that statements made by LDS leaders that are specific regarding the conception of Christ are not official (p. 135). The problem is that several church manuals have been a bit more candid than what Robinson would lead us to believe. For instance, Gospel Principles, states, “Thus, God the Father became the literal father of Jesus Christ. Jesus is the only person on earth to be born of a mortal mother and an immortal father” (p. 64). In 1972, a Family Home Evening manual gave an illustration of a man, woman and a little girl which said, “Daddy + Mommy [=] You.” Below this illustration were the words, “Our Heavenly Father + Mary [=] Jesus.”

Robinson can play all he wants with the definition of the word “literal,” but if he chooses to say that this does not mean God physically impregnated Mary, then he must concede that Elohim did not “literally” impregnate “Heavenly Mother” prior to our becoming “spirit-children.” To deny this would be to also cast doubt on the LDS doctrine of “eternal increase” whereby Mormons believe they will have the opportunity of endless celestial sex with their goddess wives.

Robinson is not much different from LDS Apostle Bruce R. McConkie in his definition of the word “virgin.” On page 466 of his book The Promised Messiah, he stated, “For our present purposes, suffice it to say that our Lord was born of a virgin, which is fitting and proper, and also natural, since the Father of the Child was an Immortal Being.”

The problem with McConkie’s conclusion is readily apparent. The definition of “virgin” means to not have had sexual intercourse with anyone. By having sex, the description of “virgin” becomes meaningless. It is both incredibly inaccurate and deceptive for a person to say he believes in the “Virgin Birth” while at the same time accepting the teaching that a God with human body parts physically impregnated Mary.

It is nowhere close to the Christian doctrine that the Holy Ghost overshadowed Mary in a nonsexual way. What becomes even more blasphemous is the idea that, according to LDS doctrine, Mary is a literal daughter of the same God who supposedly impregnated her. Is this not incest?

Salvation

We have found that in this area Robinson strays furthest away from his LDS fold. Blomberg seems to see this as he cites Robinson’s book Believing Christ. Naturally Robinson would disagree and would lay the blame, in part, on Christian ministries like ours for misunderstanding his arguments. Robinson explains on page 158 that Believing Christ was not meant to be a book of “theological precision using Evangelical terms for Evangelical readers.” Rather, it was intended for LDS readers who understand LDS language. Is Mormonism so esoteric that no non-Mormon could ever understand what he was saying in that book?

What Robinson advocates is not what the majority of Mormons we know would profess. To read Believing Christ is to readily see that Robinson disagrees with many of his fellow church members. Several times he chides the LDS Church membership (including his own wife) for misunderstanding what he feels is a correct theology. His position would carry more weight with us if he occasionally supported his view with a reference from a general authority. This he rarely does.

Robinson is incredulous that some might accuse him of being an “aberration” (p. 163). He even berates those who would attempt to support this charge by what he calls a “flurry of prooftexts culled from sources supposedly more reliable than I am on the subject of what I believe” (p. 162).

He misses the point. We are not denying what he may personally believe to be true. Instead, we merely have difficulty accepting what he says is the LDS norm. Contrary to his assumption, there are many sources that are “more reliable” when it comes to LDS orthodoxy. It should be remembered that BYU professors are not general authorities, but are merely paid employees of the church.

Unlike most Mormons, Robinson sees the futility of trusting in good works for salvation. He seems to understand the implications that if one chooses to be saved by the works of the law, it can only be done by always keeping the law. For example, on page 42 of Believing Christ, Robinson states,

“We can’t earn our way into the celestial kingdom by keeping all the commandments. We could in theory but not in practice – because you nor I nor anybody else has kept all the commandments. This is so incredibly self-evident and simple that some people can’t see it.”

One of those who apparently couldn’t see it was Joseph Fielding Smith. He declared on page 206 of The Way to Perfection, “To enter the celestial and obtain exaltation it is necessary that the whole law be kept“ (emphasis his). On the next page Smith said, “Do you desire to enter into the celestial Kingdom and receive eternal life? Then be willing to keep all of the commandments the Lord may give you.”

Robinson insists that God will reward a willingness to keep the commandments, not the actual keeping of them (Believing in Christ, p. 54). If that is so, then why is a person required to promise to keep the commandments (not just be willing to keep them) at baptism, when partaking of the sacrament, and during the temple endowment? As an employee of BYU, Robinson must remain temple worthy in order to keep his job.

Since he has certainly participated in the LDS temple endowment ceremony, we are sure that Robinson is fully aware of the threat to keep every covenant. In this ceremony the character portraying Lucifer looks at the audience and warns, “I have a word to say concerning these people. If they do not walk up to every covenant they make at these altars in this temple this day, they will be in my power!”

In this chapter Dr. Blomberg eloquently describes the Christian view of salvation and even delves into the controversial issues that have caused debate in the Body of Christ. He lists numerous passages from LDS scriptures that seem to contradict each other as well as contradict what he has personally heard from Mormons.

He concludes that conversations he has had “with numerous Mormon missionaries, Mormon friends and ex-Mormons suggest to me that an orientation toward works is still well entrenched” (HWTD p. 177). However, despite his personal experience from primary sources, he also writes, “Again, I am happy to be told that I have misunderstood the Mormon position on this issue because I am not adequately fluent in LDS terminology” (p. 179).

Since we too, have had numerous Mormons respond in a manner similar to what Dr. Blomberg has experienced, we would have asked how so many Mormons could be so confused. How was Robinson so fortunate to see what so many of his fellow members had apparently missed? In essence, Blomberg’s experience tends to demonstrate Robinson is not the norm as he claims.

Dr. Robinson is credited with what is known as the Parable of the Bicycle. We have heard several Mormons use this analogy in witnessing situations when trying to justify the role of works in the LDS salvation process. Robinson explains this “parable” on pages 30-32 of Believing Christ. He tells how daughter Sarah’s desire for a bicycle prompted him to tell her, “You save all your pennies, and pretty soon you’ll have enough for a bike.”

In the next paragraph he remarks, “A few weeks went by, and I was once again sitting in my chair after work, reading the newspaper. This time I was aware of Sarah doing some chore for her mother and being paid for it. Then she went into her bedroom, and I heard a sound like ‘clink,’ ‘clink.’” In reading this story, our attention was immediately drawn to the words “chore” and “paid.” These words clearly speak of works and reward.

When it came time to go “look at bikes,” Robinson related how little Sarah was dismayed to find that the mere 61 cents she had tried so hard to save did not come close to the price tag of the bicycle she desired. In response, her father struck an incredible deal when he told her, “You give me everything you’ve got, the whole sixty-one cents, and a hug and a kiss, and this bike is yours.” As he drove home, Robinson says, “it occurred to me that this was a parable for the atonement of Christ.”

Blomberg correctly noted that Robinson’s analogy might be close to the truth, but it is not completely sound according to the Bible. He asks, “What if Robinson’s daughter had come to the store flat broke? What if she had squandered her sixty-one cents and even incurred a small debt by borrowing and flittering away some small change from her friends? These analogies correspond more closely to the actual spiritual state of humans apart from Christ” (p. 181).

We couldn’t agree more. The problem with Robinson’s parable is that it fails to take into account the severe depravity of man. Ephesians 2:1 makes it clear that it is by the grace of God, vile sinners who were “dead in trespasses and sins” are made alive. A person who is dead is unable to offer anything.

Robinson defends his parable by insisting that the amount of sixty-one cents was an arbitrary figure. “Had she been broke,” he says, “the offer would still have been made, but the terms would have been for her heart in return.” However, an endnote found on page 223 of How Wide the Divide clarifies Robinson’s statement. It reads,

“The believer who has only forty-one cents, or twenty-one or eleven – or none – is still justified if he or she holds nothing back. It is not the quantity, but the commitment that matters. Without a commitment that translates into behavior, we are not saved. With such a commitment, be it ever so small at first, we are.”

Such a statement shows us that Robinson still does not fully comprehend what justification by faith really is. If it is indeed by faith we are justified (as so taught in a strong way by Paul), no amount of work—however little or much—can make anyone more justified in God’s sight. We agree with Dr. Blomberg when he says Robinson “comes tantalizingly close to historic Christian affirmations of salvation by grace alone but then stops just short of them” (p. 179).

Another area of concern is found in Robinson’s Believing Christ. On page 95 he tells the story of a female convert whose sordid upbringing made it very difficult for her to comply with the rigid behavioral traits Mormons are expected to follow. “For a long time after her baptism,” Robinson, notes, “this sister still swore like a trooper, even in church, and never quite lived the Word of Wisdom one hundred percent. On one occasion during her first year in the Church, she lost her temper during a relief society meeting and punched out one of the other sisters.”

Eventually this woman stopped smoking, drinking coffee, tea and got her temper “somewhat” under control. “Finally, after she’d been in the Church many years, she was ready to go to the temple” (p. 96).

Robinson then asks,

“At what point did this sister become a candidate for the kingdom?” He insists qualifying for her temple recommend had nothing to do with this. “She was justified through her faith in Jesus Christ on the day that she repented of her sins, was baptized, and received the gift of the Holy Ghost, for she entered into that covenant in good faith and in all sincerity.”

Again Robinson offers no statements from LDS general authorities to bolster his view. Twelfth LDS Prophet Spencer W. Kimball shows that Robinson’s conclusion is certainly simplistic. He wrote:

In order to reach the goal of eternal life and exaltation and godhood, one must be initiated into the kingdom by baptism, properly performed; one must receive the Holy Ghost by the laying on of authoritative hands; a man must be ordained to the priesthood by authorized priesthood holders; one must be endowed and sealed in the house of God by the prophet who holds the keys or by one of those to whom the keys have been delegated; and one must live a life of righteousness, cleanliness, purity and service. None can enter into eternal life other than by the correct door Jesus Christ and his commandments (The Miracle of Forgiveness, p.6).

How did Robinson conclude that this woman had truly “repented” while at the same time admitting she still had a long way to go in overcoming her sinful habits? Spencer W. Kimball said the repentance which merits forgiveness involves the transgressor reaching “a ‘point of no return’ to sin” which includes clearing the “desire or urge to sin” out of one’s life (pp. 354-355).

Again, while we don’t doubt that Robinson personally believes what he says, we have a difficult time finding statements from LDS authorities that agree with them.

Conclusion

Besides the unfair accusations made against the Christians who belong to the front lines and are involved with countercult ministry, it seems that Blomberg’s greatest mistake is his desire to believe that Robinson represents mainstream Mormonism. Perhaps he shouldn’t be faulted too seriously for this. However, this type of hope can lead to some seriously wrong conclusions if one only has a textbook knowledge of Mormonism.

Robinson is a clever writer who is able to make Mormonism sound like Christianity. While Blomberg is a very intelligent professor, he too often appeared to concede a point instead of making Robinson support his views from authoritative sources. No doubt Robinson would argue that he did support his views from the standard works. The problem is he usually gave his interpretation of those passages instead of quoting his leaders who supposedly have been called to do that for him.

Since the book was designed to discuss the differences between LDS theology and Christian theology, we regret that Robinson was chosen to speak on behalf of the LDS faith. While we have no doubt that he is putting to print what he may have in his heart, he absolutely does not represent the normal LDS position on many points.

This book would have better served the public had an LDS general authority been chosen to represent the Mormon position. Unfortunately, the only men in the LDS Church who seem to have any authority to discuss such issues choose not to do so.

Unlike the prophets and apostles mentioned in both the Bible and Book of Mormon, modern LDS leaders refuse to engage their critics in such a manner, whether official or unofficial. Instead of acting more like CEOs, it would be nice to see the LDS leaders follow the example of the biblical prophets and apostles by defending their faith with those who have done their homework.

Instead of following the footsteps of the Book of Mormon characters Abinidai or Helaman, or the biblical characters Isaiah or Paul, the LDS leaders choose to allow the unofficial rebuttals like those of Robinson’s or those at the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS).

If the LDS Church claims its authority is represented in the existence of a prophet, two counselors, 12 apostles, and numerous Seventies, then why didn’t one of these general authorities write this book? We feel the answer is quite simple. If these unofficial defenders of the LDS Church make a good case, then the Church has benefited at no risk. If they make a poor presentation, then the blame can be shifted to the individual writer. This allows the LDS Church organization to be free from all responsibility.

Blomberg more than once had to admit that the way he understood Mormonism was much different from how Robinson presented his case. For instance, he writes on pages 53-54:

“I find Robinson’s views of [biblical] inspiration considerably less objectionable than most Mormon explanations of that doctrine…To me, Robinson’s explanation seems to be quite a stretch in understanding the meaning of Joseph’s claims to be ‘translating,’ and they differ remarkably from what Mormons have traditionally seemed to hold. But I welcome them as a substantial improvement over what I previously understood (rightly or wrongly) Mormons to believe” (emphasis ours).

We welcome them too. More than once we were excited to read that Robinson seemed to have a better grasp on spiritual truths than do most Mormons. However, many of those who read How Wide the Divide? will be unaware of the differences between Robinson’s personal beliefs and that of LDS orthodoxy.

Just because Robinson appears to be closer to Christianity in some regards does not mean that Mormonism is in any way closer to Christianity. The fact of the matter is Mormonism is going to remain the religion its leaders make it to be, not what individual Mormons like Robinson want it to be. Despite Robinson’s dressing up of LDS doctrines to make them seem compatible with historical biblical Christianity, the similarities between the two faiths are less than what the authors make them out to be.

Although Blomberg is an excellent expositor on the biblical subject matter, we feel he too was not the proper choice to co-author this tome. On too many occasions his writing was so generic that we could visualize many Mormons nodding their heads in agreement, saying, “That’s what we believe too!” As previously stated, too often he allowed Robinson to get away without compelling him to either define his terms or support his views with statements from LDS leaders. Had he done so, we are confident the divide would have been much wider than supposed.

Mormon Minimalists

Since the publication of How Wide the Divide, a new term has been given to Mormons such as Robinson who seem to be distancing themselves from the LDS teachings of the past. Rather than being described as traditional Mormons, they are being classified as “minimalist” Mormons. Technically a minimalist is a person who “advocates action of a minimal or conservative kind.” If this term is being used to rightly classify Robinson’s position as being in the small minority we would agree. However, the book does not make this clear.

Instead, Robinson portrays himself as doctrinally traditional. This being the case, we would have been much more comfortable with How Wide the Divide had the cover stated this. Perhaps instead of a subtitle that read, “A Mormon and an Evangelical in Conversation” it would have been more appropriate to have “A Minimalist Mormon and an Evangelical in Conversation.”

Because this is not made clear, we feel the book will not be a help to Christians who are seeking what actually divides Christians and the great majority of Mormons on these very important issues.