“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” — 1 Corinthians 13:11

When I was a young boy of about 10, a favorite activity was to spend time in my backyard attempting to hit whiffle balls over the fence and into the front yard. I would toss a ball up in the air and swing at it with a wooden bat. Each time a ball left my make-believe playing field, it was nothing less than a walk off home run to win yet another 7th game of the World Series! (“And the crowd goes wild! Johnson does it again!”) Hero time.

In addition, my neighbor Jerry and I spent countless hours pitching these plastic balls to each other as well. If the ball went over the pepper tree and landed in the front yard, the batter would take his customary trot around the bases with his hands raised. I remember even keeping track of the number of home runs I hit. One year, I counted more than 100 dingers! (It was nothing less than an MVP season!)

By the time I got to be 12 or 13 years old, I don’t remember playing this imaginary game anymore. My friends and I had moved on to other things, like taking our Schwinn bikes “off roading,” going to the Rec center to participate in pick-up basketball games, and visiting the local cinema each week to see the latest movie. The older we got, the more we put away childish activities. By the time we were 16 or 17, we had ceased most child’s play and even got jobs to pay for our entertainment.

Undoubtedly, not everyone grows up. Don’t we all know someone who continues to live in a land of fantasy, believing they are the hero of every game and battle they pretend to be in?

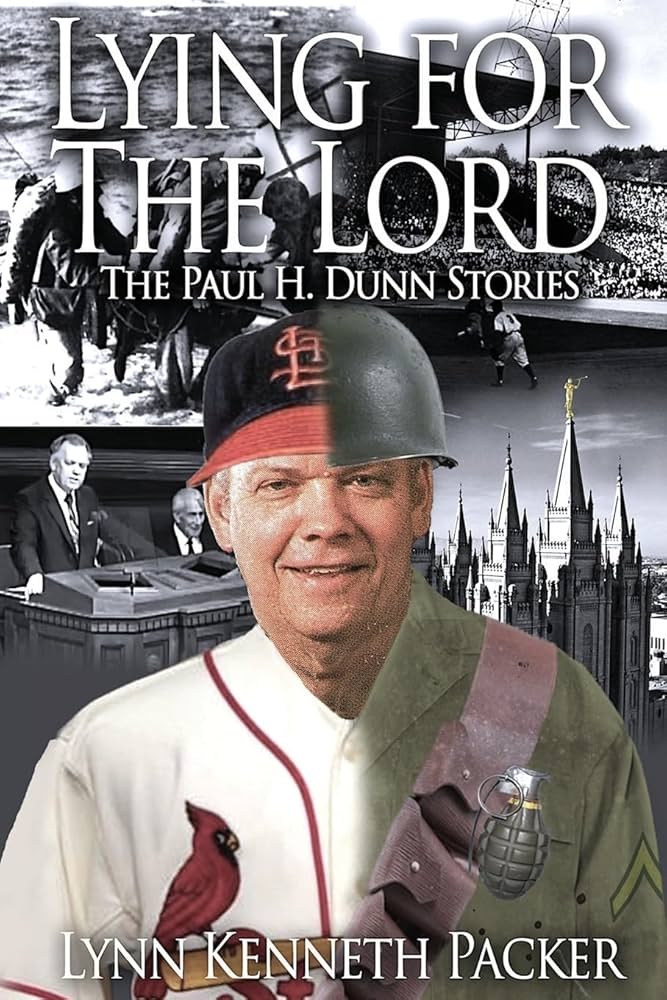

Paul H. Dunn, a former member of the Quorum of the Seventy in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is someone whom I believe never learned to quit trying to be the hero of every story. A book written by Lynn Packer titled Lying for the Lord: The Paul H. Dunn Stories details the deception of this Mormon general authority and just how dangerous it is to live in a make-believe world.

A Dynamic Story Teller

Paul H. Dunn (April 24, 1924 – January 9, 1998) filled LDS fireside meeting rooms throughout the 1970s and 1980s with his entertaining stories. He was also a regular speaker at the semiannual General Conference sessions between 1964 to 1987; in fact, Dunn took a spot behind the conference pulpit twice a year from October 1964 to April 1973. He was asked to speak less often from 1974 through 1987, but this general authority continued to average one conference talk per year.

Never one to be without a sensational story safely tucked in his back pocket, Dunn was considered one of the most dynamic speakers the church had to offer. With a variety of embellished stories, Dunn made other general authorities–many of whom were monotone in their delivery with no ability to keep easily-distracted listeners entertained–seem second class.

At the Utah Christian Research Center located in Draper, UT, we have a 1969 1st edition copy of The Miracle of Forgiveness on display. There is nothing really special about a 1st edition edition by the 12th president of the church because so many copies were produced. However, the inside cover of this particular copy features an autograph by the author. Again, this is not uncommon, as I personally own five other copies signed by Kimball. He must have signed hundreds, if not thousands, of copies of his signature book.

So why do I point out this particular copy? It’s because Kimball inscribed it to Paul H. Dunn, which I’m sure is the only copy ever Kimball autographed to him. Inscribed are these words: “To the Paul H. Dunn with affection Spencer W. Kimball.”

An Exposé of Paul H. Dunn

A story in the February 16, 1991 edition of the Arizona Republic reads:

“Among Mormons, Elder Paul H. Dunn is a popular teacher, author and role model. As a prominent leader of the Church . . . for more than 25 years, he has told countless inspirational stories about his life:

Like the time his best friend dies in his arms during a World War II battle, while imploring Dunn to teach America’s youth about patriotism.

Or how God protected him as enemy machine-gun bullets ripped away his clothing, gear and helmet without ever touching his skin.

Or how perseverance and Mormon values led him to play major-league baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals.

But those stories are not true.”

Lynn Kenneth Packer is the nephew of Boyd K. Packer, the former President of the Quorum of the Twelve before his uncle passed away in 2015. A journalist by trade, Lynn Packer investigated Paul H. Dunn for more than a decade in an effort to determine the veracity of his stories. In 2015, Packer culminated his research with a book titled Lying for the Lord: The Paul H. Dunn Stories.

Nobody will ever confuse this book as a possible contender to win the Pulitzer Prize. It’s not perfectly written. For example, despite his writing/broadcast career on a local Utah news station while serving as an adjunct journalism professor at the church-owned Brigham Young University, Packer would have benefitted from having a good editor mark up his 380-page work. Indeed, there are dozens of grammatical and spelling mistakes littered throughout the book.

Yet this drawback does not take away the power of Packer’s writing, and for the record, I highly recommend it. Due to the limitations of an online book review, I cannot cover every single detail. Still, I will liberally cite the author throughout while exploring an amazing tale of deceit spun by a man who was looked upon as having authority in the LDS Church.

A pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals?

Dunn’s most obvious lie–one that should have been publicly exposed much earlier–was his deceptive claim that he pitched for the MLB St. Louis Cardinals. Packer explains:

“In conflicting speeches Dunn claims to have signed a contract with the St. Louis Cardinals and to have been drafted into military service when he was 18. Both could not be true. It turns out that neither was true. The minimum draft age was still 21 when he graduated; it would not be lowered to 18 until December of that year. Neither was it true that he signed with the St. Louis Cardinals even though he said otherwise” (33).

Dunn reported that one of the places where he played minor league ball for the Cardinals was in Pocatello, ID. According to a favorite story, Dunn said he was pitching in the 8th inning of a championship playoff game with no score when the opposing team’s batter hit a sharp single to the center fielder. It should have been an easy score for the runner on second, yet the ball was apparently hit so hard that he was thrown out in a close call at the plate. As Dunn describes it, this player began to scream obscenities at the umpire, which got him ejected from the game. As Dunn returned to the mound, the ump supposedly told him, “Paul, forgive him, he doesn’t understand.” (Perhaps reminiscent of Jesus’s words, “Forgive them, Father, for they do not know what they do.”)

Like his other baseball stories, this story was absolutely made up. On page 38, Packer writes,

“Paul Dunn did not pitch the championship game. His name did not appear on the Cardinals’ official roster, not even on the list showing players who played fewer than forty-five innings. Dunn’s name appeared in no newspaper box score. It is nowhere to be found in the extensive files of the Cardinals’ parent organization.”

He adds:

“The facts are straightforward. Dunn never played in a regular season game with a professional baseball team. He never had a professional baseball career. He pitched part of a Class C exhibition game for a losing cause, and would have been paid a modest salary for a week’s service before being cut.”

At the April 1980 General Conference at the tabernacle. Dunn explained at the end of the talk how willing he was to share his faith with his fellow players. The story begins with his manager knocking on Dunn’s hotel room door:

“He said, ‘Paul, may I come in?’

And I said, ‘Please do. What’s the matter?’

He said, ‘Close the door, and whatever you do don’t tell the others I came.’

I said, ‘Well, I won’t.’

He responded: ‘I’ve been watching you for these past two months. You know the Lord, don’t you?’

I said, ‘I think he’s my friend.’

He said, ‘Would you help me find him?’

We sat down in the room, and for over two hours talked about God, the Eternal Father, and his Son, Jesus Christ. Tears began to form in his eyes.

I said, ‘Danny, have you ever prayed?’

He said, ‘No.’

I said, ‘Would it offend you to pray with me?’

‘Well,’ he said, ‘not if you will pray.’

I said, ‘I would be honored.’

So together we knelt down beside my bed, and talked to Heavenly Father. We took time-out. And as we arose from our knees, he pushed back the tears, threw his arms around me, almost choked me to death, and said, ‘Thank you, thank you. Could we do this some more?’

I said, ‘As often as you would like.’

We did on several other occasions. But you know what was interesting. Before the season ended, several other knocks came at my door. One night it was the first baseman, then the shortstop, and the left fielder. And each in his own wonderful way said, ‘Don’t tell the others’” (Ensign, May 1980, 39).

It sounds so quaint, almost Saturday Evening Post-like. The problem, however, is that Dunn did not play organized baseball for a professional team at any level. And it is something that the LDS Church must have known. Packer writes that “in 1970 a writer for the church’s own New Era magazine checked out Paul Dunn’s baseball stories and found they were not true. . . . later Dunn tried to portray his stories as embellishments.”

Because of this, Dale Van Atta, who later became an investigative reporter for the Deseret News, claimed that Dunn’s lies ended up costing the general authority any chance to move from Seventy to Apostle in the LDS Church (40). In 1977, Norman Olsen—the president of the LDS mission in St. Louis—

“invited Dunn to bring the Osmonds to St. Louis for a Mormon Night at a (St. Louis) Cardinals baseball game at Busch Stadium. Because Dunn had played for the Cardinals, Olsen thought it would be a nice surprise to present Dunn a plaque inscribed with the years he played, in front of thousands of fans. So Olsen had missionaries go to the Cardinals’ vast baseball library to get that information. To the missionaries’ amazement, the librarian could not find a trace of Dunn pitching for the major league team or for any of its multiple farm clubs. The plaque idea was quietly dropped, but the word got out” (220).

Was the church’s complicity a result of Dunn being a popular speaker who garnered the attention of the LDS people? Was it because confronting one of their own would have caused embarrassment to the LDS leadership? Whatever the reason for letting the lies slide, Paul H. Dunn did not receive any discipline for his made-up heroic baseball stories during the entire three decades serving as a Seventy, including as a member of the Presidency of the Seventy from 1976 to 1980.

A War Hero?

Another favorite topic was when Dunn would tell a variety of World War 2 stories involving battle scenes he never experienced. While It is true that Dunn was a soldier in the war, his unit’s adventures were on the tame side. Among other tales, Dunn claimed that he fought in the Pacific battle of Okinawa in 1945. In a general conference talk given in October 1966, Dunn said:

“It was just 21 years ago on another Easter morning when a great armada of ships assembled in the bay off the island of Okinawa. And on that Easter morn as I looked upon the faces of those who were to take the beach, one of the great, great questions of all the ages seemed again to be registered by those men. ‘What hope is there in the future?’

The answer came to me, I believe, in the midst of one of my darkest hours. As I pushed ashore with my buddies, I crawled a few feet into the sand, and there I found a young soldier in the last moment of this life. I didn’t know his name, nor could I tell you to which faith he belonged. As I tried to give him a little bit of comfort, his last words were these: ‘Out of this filth, death, destruction, will come a new world and a new way of life.’

Just as the soldier died, Dunn noticed a patch of Easter lilies ‘signifying to those who would observe the new birth and a new way of life. It was later I discovered that Okinawa was the Easter lily capital of the Orient.’”

In one church magazine article, Dunn explained how his unit started with 1,000 soldiers in San Francisco but there were only six of the soldiers left two and a half years later. In that article, he detailed one skirmish he was in and said at the end,

“As I went down another machine gun burst came across my back and ripped the belt and the canteen and the ammunition pouch right off my back without touching me. As I got up to run, another burst hit me right in the back of the helmet, and it hit the steel part, ricocheted enough to where it came up over my head, and split the helmet in two, but it didn’t touch me. Then I lunged forward again, and another burst caught me in the loose part of the shoulders where I could take off both my shirt sleeves without removing my coat, and then one more lunge and I fell over the line, into the arms of one of the dirtiest sergeants you ever saw. He’d watch the whole encounter, and he said, ‘Paul, you sure are lucky.’ He said, ‘Follow me,’ and I crawled back up, and I was the one of the 11 who had even make it the first 100 yards. Lucky? Oh, you call it what you want. I’d had verification after verification. A thousand such incidents happened to me in two years of combat experience” (New Era, August 1975, pp. 6-8).

This number is repeated in his book Discovering the Quality of Success:

“Out of the one thousand men in the second battalion of the 305th regiment that started in San Francisco, only six of us made it to the end of the war. And you know my luck, I was grateful to be one of the six” (65).

Yet this and his war stories were not true. Concerning the story above Dunn’s involvement in Okinawa, Packer writes,

“According to military records, and reflected in a letter young Private Dunn wrote home, his division did not even participate in the initial invasion of Okinawa. . . . Its first action did not occur until April 24, more than three weeks after the Easter landing. Even then, the action did not involve Dunn’s 2nd Battalion of the 305th regiment, which arrived even later, returning from garrison duty” (104).

Dunn loved to recount how his friend Harold Brown died in his arms after a battle at Okinawa in 1945. Part of the often-told story went like this:

“‘Harold, are you there? Are you all right?’

No response. the kind of warfare we fought in the Pacific prevented you from getting out of your hole. . . . I said, ‘You hold on, Harold, and I’ll get you out of there in the morning. There’s an aid station about a thousand or two thousand yards behind.’

‘I’ll try,’ was his response. ‘I’ll try.’

And all night, I called over words of comfort. And the temperature dropped and it became very cold. And it rained and it rained, and the enemy tried several suicide attacks into our line. Somehow we held out. Just as the dawn commenced to break, I let the men around me know that I was going to try to crawl over to where Harold was. And so I did across that muddy ground. And Harold was now almost completely submerged in his foxhole. Just his head and neck showed above the surface of the water. The water had filled up his hole” (116).

Packer continued:

“Dunn described pulling his friend out on that muddy bank, putting Brown’s head on his lap, and trying to wipe the mud and caked blood from his face. He counted sixty-seven shrapnel wounds in his friend’s body, Dunn said, some large enough to put his hand in. He offered the little comfort possible under those conditions, and said, ‘Now Harold, hold on, and I’ll get you back.’ ‘No,’ Brown replied, ‘This is the end.’ . . . .” (116)

Dunn describes the final words given by the soldier as he faded away:

“‘If you live through this terrible ordeal, would you someday tell the young people of America . . .will you tell them for me, that it’s a pleasure for me to lay down my life for this country? . . . If it’s convenient, someday would you go tell my mom how it all happened? My mom is the worrying kind. And she’ll kind of want to know that I lived true to my principles to the end.’ He died just a few minutes later in my arms” (116).

Dunn then described how he carried Brown’s body back to the aid station and helped bury him. Later, when he returned from the war, Dunn claimed he visited his friend’s family. Yet, as Packer relates on page 117, “Dunn knew that Brown literally lived in Odessa, Missouri, having returned intact to the place where he grew up.” Years later the very alive Brown told Packer who interviewed him, “That’s a new one to me” and suggested that perhaps Dunn had mistakenly used his name rather than the real victim. Just as they had to know Dunn’s baseball stories were full of lies, church leaders must have known that Dunn’s war stories such as this, were completely fraudulent.

After all, it would not have been hard for an organization with so many ready-made resources to determine how Dunn was a fraud And they had every incentive to know if one who represented them as a leader was genuine or just blowing smoke. Consider:

“Dunn was confronted with his Brown-dying-in-a-foxhole story by Harry D. Pugsley, who investigated on behalf [of the] LDS Church. Aware that a reporter was about to debunk Dunn’s war stories, church officials assigned an attorney to look into the matter. Faced with the reality that Brown was still alive, Dunn simply changed his story—a little. He told Pugsley that he ‘goofed’ when he used the name Brown. It was actually Ralph Cocroft who had died that May 11, 1945” (118).

Yet as Packer reported on page 119, Cocroft

“had died instantly, not in the arms of any buddy (who meanwhile tallied some sixty-seven wounds). Nor did he utter patriotic words to be relayed to America’s youth. In other words, the name ‘Harold Brown’ was not simply a stand-in for Ralph Cocroft in Dunn’s dramatic tale. Also, Cocroft could not have died in the action Dunn repeatedly described as having occurred on May 11. Cocroft was killed two days after Dunn’s May 13 letter was written.”

Determining the lie from this particular story is what allowed Packer to determine that Dunn had made everything up:

“It was when I found Harold Brown alive and well, living in Odessa, Missouri, that the scales were tipped. Most of Dunn’s stories had been difficult to pin down 100% given his denials and ostensible evidence. But Brown was living proof he was not dead” (124-125)

It does not appear that there was any war story Dunn told that can be considered true! A follow up by church authorities would have gone a long way to prevent further embarrassment down the road. As Packer reported:

“Dunn had no Purple Heart, which he would have won had he been wounded, as he claimed, in any of the battles. In fact only fifteen men in his unit won Purple Hearts, an indication of the relative safety in which company personnel usually found themselves. (The First Sergeant in Dunn’s regiment said, ‘If you got cut on a tin can you could get a purple heart.’ Sgt. Piano, who knew Dunn, said he would have received a Purple Heart had his wrist been cut by a bullet like Dunn claimed.)” (309).

The AFCO Scheme

The deceit of Paul H. Dunn in a Utah business dealing cost many Latter-day Saints their life savings. This is not the first time an incident like this took place with an LDS leader. For instance, Joseph Smith caused many early Latter-day Saints to lose their investments in the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company in the late 1830s. SOURCE

Over the years the state of Utah (the state where the headquarters of the church is located) has been home to a number of fraudulent investment schemes, often with Latter-day Saints preying on trusting fellow members who attended their wards. Utah is, as the attorney general put it in 2019, the “fraud capital of the U.S.” Even the state’s web site warns Utahns to be aware of such deceit. (See here.)

Many “Ponzi” schemes are built on enterprises with no real end product. Investors are promised incredible returns to their investment, a great temptation for the greedy looking to make a quick profit. Those who invest early might get fabulous returns on their money; however, those who enter the investment later can lose everything when the company falls apart.

During the mid part of the 1970s through the early 1980s, Latter-day Saints Grant Affleck and Carvell Shaffer put together a real estate resort complex called “AFCO Enterprises,” which had been contrived from Affleck’s name. AFCO attempted to get Latter-day Saints to take out high interest loans on their homes so they could make money. Having a general authority such as Paul H. Dunn vouch for the company resulted in many Latter-day Saints letting down their guard and eagerly investing.

In fact, many investors had mistakenly thought Dunn was an apostle, a higher position than a Seventy, as he was just that popular. The apparent rationale was that, if an apostle of the LDS Church had faith in this company, so should they. There must be nothing to fear. As Packer explains,

“Typically AFCO salesmen asked their targets to purchase an investment for $50,000. The investors would be paid 25 percent interest with their investments secured by trust deeds on undeveloped lots in Glenmoor Village. Few Mormon families had $50,000 lying around. On a national scale, Utahns ranked low when it came to savings, partly due to larger families and lower wages than the national norm. Most were inexperienced investors in either mutual funds or real estate. Finally, Mormons tend to trust their leaders—bishops such as Affleck and especially general authorities such as Dunn. For many potential investors, the equity in their homes represented their greatest wealth. Affleck targeted that saying, “Awaken the sleeping giant in your home.” In other words, “Tap your home equity and put it to work.”

As the adage puts it, always be cautious in investing in anything that sounds too good to be true. Or, as it has been said, the fool and his money are soon parted. Generally, borrowing money from one’s home to invest in risky ventures is considered foolhardy. Yet, though there had been ample warning signs, AFCO continued to operate its shady dealings into the early 1980s. Affleck and Shaffer, meanwhile, used AFCO to plunder the life savings of scores of Mormon families. Packer wrote,

“By October 1981, AFCO became deeply submerged in red ink. Affleck’s pressure on his sales force mounted for new investors were needed simply to pay the interest on huge and increasing debt. One bank note required a monthly interest payment of $141,000. AFCO, in short, had become a Ponzi scheme where investment money did not go into a project, but to pay off previous investors’ debt. Word began to spread that AFCO was in trouble. A woman about to lose her home confided her fears to her bishop. A local banker became increasingly appalled as his customers shrugged off his advice and invested in AFCO. As a reporter for KSL-TV, I heard those rumors and encountered little difficulty in discovering the breadth of the fraud: unlicensed salesmen, worthless collateral, and uninformed investors. Salesmen were telling investors their money was safe when the the risk was actually sky high. But as fast as I could investigate and write the story, I learned that this story was unbreakable, at least at the LDS Church-owned KSL” (191)

As the ruse was uncovered by federal authorities, Dunn claimed that he had resigned from the company in 1978 because his connection to the LDS Church had been exploited. This claim was a lie as Dunn had continued with the company, even receiving a new fancy car every year through 1982 while regularly attending the company’s board meetings into 1982. Packer explains,

“Despite Dunn’s 1978 resignation, the Wall Street Journal reported Dunn ‘continued to have ties with AFCO until it entered bankruptcy proceedings in 1982.’ (Later, in a deposition, Dunn admitted attending board meetings after 1978, but only to deliver prayers or inspirational messages” (201).

When Affleck took the witness stand in 1984 to testify in his own defense, he admitted that he had previously lied about Dunn resigning in 1978 to protect his church leader. Despite this admission, no indictment was brought against Dunn. Meanwhile, “Dunn not only squeaked past criminal charges but he also managed to avoid testifying in court as a witness either for or against Affleck” (201).

Packer was put on the hot seat while investigating the many problems with AFCO. In November 1981, KSL news director Spence Kinard received a call from Dunn telling him the TV station should not report on how Dunn had remained a board member past the 1978 time when he supposedly got out. The call came from Dunn himself using his position as a general authority!

“Kinard said the call stood out because it was only the second time he had received a call from a General Authority to kill a story. The first was a call he received from Gordon B. Hinckley about a story involving Salt Lake Tribune publisher Jack Gallivan. ‘He argued we ought to kill the story,’ Kinard said about Dunn’s call. Kinard said he told Dunn the station had been ready to do a story, but had not decided to air it” (215).

It wasn’t until the next year when the news was released about how AFCO went belly up and could not pay the investors at the cost of millions of dollars. The delay in reporting this was detrimental to many new investing families

“By pressuring KSL to delay breaking the AFCO story—between October 1981 and March 1982—dozens of families continued to invest at a time there was no chance AFCO could pay them back. At the same time, Dunn worked to keep worried investors from going to authorities. When AFCO quit making payments investors began getting demands for payment and notices of foreclosure. Dozens of families were terrified” (221).

During those critical years from 1978 to 1982, Dunn continued to block for the AFCO organization by calling off frustrated investors who had threatened to make legal claims against the company. At the same time, Dunn privately was pressuring the company’s leaders to serve his own interests by paying back the money he had invested with them. As Packer explained,

“Dunn convinced the group to back off, to give Affleck a chance to raise outside capital. But Dunn, himself, did not back off. Instead of telling Affleck to immediately pay those investors, he asked Affleck to repay the money Dunn and his family had invested” (222).

Dunn had invested $57,000 of his family trust (for 18% interest) along with a $22,000 bank note and a co-signature on a $5 million loan. While Dunn claimed that his request for funds “fell on deaf ears,” Packer’s research contradicts this by saying that “records obtained during my search of the bankruptcy files revealed otherwise. After the investor meeting and before bankruptcy Affleck gave Dunn a series of checks” (222).

More than 650 investors had lost $20 million of their investment money, an average of more than $31,000 per investor. In addition, a number of investors’ homes were repossessed because of the debt, with a number of people becoming financially ruined.

Protected by the Brethren

Later in the mid-1980s, when Packer had gathered sufficient information to print an article with the UPI wire service, he received no support from different media outlets or church organizations. After a number of run-ins with his supervisors while working as a BYU adjunct journalism professor, Packer agreed not to report on the information that he had uncovered because he had been threatened with the loss of his job. This was not good timing, as Packer’s wife had just been diagnosed with cancer and he needed the health insurance policy. The deal for Packer to remain silent was easy to make since protecting his family’s financial interests became his top priority; the story on Dunn would just have to wait.

In February 1988, Packer was not offered a contract for the 1988/89 academic year despite the unwritten agreement he had made with school officials for him to keep his job in return for silence on the power-packed story. Packer wrote, “I figured that BYU must have thought it had helped Dunn buy enough time to kill the UPI story. Or that it never got a message about the quid pro quo agreement” (292). A month later (March 11, 1988), the BYU leadership changed its mind and offered Packer another contract for the following year, though his name was taken off the university’s catalog and phone directory.

The next year (April 1989), the liberal LDS organization Sunstone Foundation offered Packer a chance to present a paper covering his research at an upcoming symposium. Based on his own research, Dan Rector–the president and editor of Sunstone Magazine– reached out to Dunn to invite him to give a public confession or apology. Dunn refused, and then Rector backed off on the invitation that had been made to Packer. Two apostles, David Haight and James Faust, then asked to meet with Packer who provided them with the paper he had wanted to deliver at Sunstone. The church’s investigator, Harry Pugsley, finished his report just a few days before the October 1989 general conference.

What came next should not come as a surprise. At the Saturday afternoon conference session, Thomas S. Monson–a member of the First Presidency–read a prepared text that said “we acknowledge the General Authorities of the Church, all of whom are in attendance except Elders…” Packer provided the rest of the account:

“At that point there was an empty space left in the prepared text. When he read it, live, he continued ‘except Elder Paul Dunn who is at home at the advice of his doctor, recovering from surgery.’ At the same session it was announced that sixteen members of the First and Second Quorums of the Seventy were released from their ecclesiastical duties and given what the church calls ’emeritus status.’ They were released for reasons of age or health. Paul Dunn’s name was on the list. Thus it came to pass that the church had dealt with the Paul Dunn problem. At the last minute he was included in a batch of leaders who had known, for several months, they were about to be released because they reached age 70. Dunn was 65. There was no apology, no mention of any discipline, although, privately he had been sanctioned” (296).

A little over two years after he had been released from his church duties, on October 27, 1991, Paul H. Dunn published a letter in the Church News. It read in part:

“I confess that I have not always been accurate in my public talks and writings. Furthermore, I have indulged in other activities inconsistent with the high and sacred office which I have held. For all of these I feel a deep sense of remorse, and ask forgiveness of any whom I may have offended” (313).

The “apology” did not satisfy Packer, who “noted he [Dunn] had not used any words like lie, fake or fabricate. It was still a long way from admitting he made up the stories. I wondered out loud whether the published letter had been extracted from him. It sounded to me like it had” (313). Nothing has ever been admitted by the church for its coverup over many years of the actions of Paul H. Dunn.

In his 1987 book titled Variable Clouds, Occasional Rain, With a Promise of Sunshine, Dunn wrote the following:

“Nothing brings great freedom than the truth, for with truth we are free from ignorance, bigotry, and sin. . . Truth is, in reality, the most valuable of gifts; it is, verily, tough as nails; it is, truly, the best and safest course to follow. . . It is my hope that we will always seek truth and be wise in our use of it” (59-61).

Despite his braggadocio touting the importance of truth, this general authority did not live by his own words. Such a person is called a “hypocrite, ” or two-faced. Meanwhile, there is good evidence in the post-general authority days of Paul H. Dunn that he couldn’t even find solace with his wife, for there were accusations from three different women who claimed to have had affairs with Dunn–though he denied the charges (366). While the church leaders who investigated could not prove the charges, they barred Dunn in July 1991 from speaking at any more church events. His days of fraudulent story-telling was over.

Meanwhile, it appears that Dunn may have lost his faith in the LDS Church, both with doctrines as well as church history. At the end of his life, Dunn became friends with a journalist named Randy Jernigan in 1996; the two shared their doubts together. For instance, Dunn had a problem believing there was a preexistence–an important teaching in Mormonism–as well as the historicity of the Book of Mormon. Jernigan was cited as saying:

“A lot of the time he did not believe what he was teaching. The thing about celestial marriage sort of bothered him. He told me one time he had a rough time with several scriptures in the New Testament about there not being marriage and family relationships in heaven. He had prayed about it and never really got answers. He never got answers to a lot of things he bore testimony to” (363).

In 1998, Paul H. Dunn passed away ignominiously. There is no indication that he ever came to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ but rather went to his grave having serious doubts about the truthfulness of Mormonism.

Conclusion

Apostle Bruce R. McConkie once explained how God gives “discernment” to the leaders of the LDS Church by God. In his book Mormon Doctrine, McConkie wrote that “the gift of the discerning of spirits is poured out upon presiding officials in God’s kingdom; they have it given to them to discern all gifts and all spirts, lest any come among the saints and practice deception . . . Thereby even ‘the thoughts and intents of the heart’ are made known” (197).

As mentioned earlier in this article, Spencer W. Kimball could not discern the lies that Paul H. Dunn was already telling in the 1960s. Otherwise, why didn’t Kimball write a note in Dunn’s copy of his book that said something such as, “Paul H. Dunn, here is a book you ought to read carefully. Repent of all your sins and don’t commit them again. Spencer W. Kimball”?

Christian apologists Jerald and Sandra Tanner made this case in a booklet they wrote on Dunn:

“After the General Authorities of the Mormon Church discovered that Paul H. Dunn had been giving false information in his talks, they decided that the matter should not be known by the membership of the church. The people, they reasoned, must not discover that a man whom they had trusted as a church leader was guilty of fabricating stories” (What Hast Thou Dunn? 1991, 15).

Like the Tanners, I maintain that there is no way that the church was ignorant about Dunn’s fables and folklore, including his talks given at general conference sessions. I don’t believe the leadership released Dunn from his general authority position primarily because of “health” reasons. Instead, it seems clear that he was let go because the information being uncovered by Packer that embarrassed them and their religious organization. And once the truth did come out, shouldn’t the leaders have officially apologized?

The Paul H. Dunn affair is just another deflection of the LDS Church. Other examples where the LDS leadership never apologized include the Mountain Meadows Massacre, the denial for more than a century of black holding the LDS priesthood, and the purchasing of fake documents (and cover-up) created by the forger Mark Hoffman, among a number of other embarrassing examples. The primary motivation of the leaders always seems to be to protect the church, at all cost. These men have no guilt in washing their hands in the proverbial wash basin to abdicate themselves from any implied guilt.

It’s a very sad story, indeed.

Some of Dunn’s General Conference talks (not all talks are listed, with talks given before 1971):

- Apr 1971 – Young People–Learn Wisdom in Thy Youth

- Oct 1971 – What Is a Teacher?

- Apr 1972 – Know Thyself, Control Thyself, Give Thyself

- Oct 1972 – “Strengthen Thy Brethren”

- Apr 1973 – The Worth of Souls is Great!

- Apr 1974 – Parents, Teach Your Children

- Apr 1975 – A Time for Every Purpose

- Oct 1975 – “Oh Beautiful for Patriot Dream”

- Oct 1976 – “Follow It!”

- Oct 1977 – We Have Been There All the Time

- Apr 1979 – “Because I Have a Father”

- Apr 1980 – Time-Out!

- Oct 1981 – Teach “the Why”

- Oct 1983 – “Honour Thy Father and Thy Mother”

- Apr 1987 – By Faith and Hope, All Things Are Fulfilled

You must be logged in to post a comment.