Note: The following was originally printed in the May/June 2024 edition of Mormonism Researched. To request a free subscription, please visit here.

Published 9/26/2024

Just three years after Brigham Young and the first Latter-day Saints arrived in Utah in 1847, the board of regents at the newly formed University of Deseret (later becoming the University of Utah in Salt Lake City) began work on inventing a 38-character alphabet influenced by the 19th century Pitman Shorthand. Young believed this would make it easier for people to learn to speak English.

In 1852, Young commissioned his secretary George D. Watt, the first convert to Mormonism from the British Isles in 1837 and the stenographer who compiled the 26-volume Journal of Discourses, to head the project.

Young complained,

“But as it now is, the child is perplexed that the sign A should have one sound in mate, a second sound in father, a third sound in fall, a fourth sound in man, and a fifth sound in many, and, in other combinations, sounding different from these, while, in others, A is not sounded at all. I say, let it have one sound all the time. And when P is introduced into a word, let it not be silent as in Phthisic, or sound like F in Physic, and let two not be placed instead of one in apple” (Journal of Discourses 1:70).

In 1853, the board of regents created the Deseret Alphabet, with 38 symbols to sound out every syllable in English. In essence, the Deseret Alphabet is nothing less than a syllable-by-syllable code to sound out English words.

On April 10, 1854, the First Presidency stated,

“The Regency has formed a new Alphabet, which it is expected will prove highly beneficial, in acquiring the English language, to foreigners, as well as the youth of our country. We recommend it to the favorable consideration of the people, and desire that all of our teachers and instructors will introduce it in their schools and to their classes. The orthography of the English language needs reforming—a word to the wise is sufficient” (Messages of the First Presidency 2:130. Italics in original).

In 1855, several schools in the Utah Territory began to teach this new alphabet. Three years later, Young wrote a letter to the German Frederick Schoenfield about “reforming our language” through the new system that “would represent every sound used in the construction of any known language, and, in fact, [be] a step and partial return to a pure language which has been promised unto us in the latter days.”

The “pure language” referenced by Young was the “Pure Adamic” tongue, which God supposedly used to communicate with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and is destined for use in the last days.

Disruptions like the Utah War and the Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1857 stalled the project. Still, in 1859, the alphabet was utilized to produce an article in each issue in the church-owned Deseret News while church records were exclusively kept in the alphabet from 1859 to 1860.

The unique styling of the “type metal” used for creating the characters was difficult to produce. Due to the start of the American Civil War, creators of this type who lived in St. Louis were not able to manufacture sufficient sets of the characters. Thus, Young’s secretaries and the Deseret News journalists were forced to return to English in 1860. When the war ended in 1865, the campaign to use the Deseret Alphabet resumed.

On February 12, 1868, the alphabet’s fonts were finalized; on August 19th, the Deseret News published an editorial explaining advantages to the new alphabet that “to the eye to which they are familiar” is “beautiful.”

Another benefit mentioned in the editorial is that the youth who were reading approved materials in the Deseret Alphabet would not succumb to the “licentiousness of the press,” thus minimizing “much of the miserable trash that now obtains extensive circulation.” The editorial added that “it would be better, in our opinion, if they never learned to read the present orthography. In such a case ignorance would be blissful.”

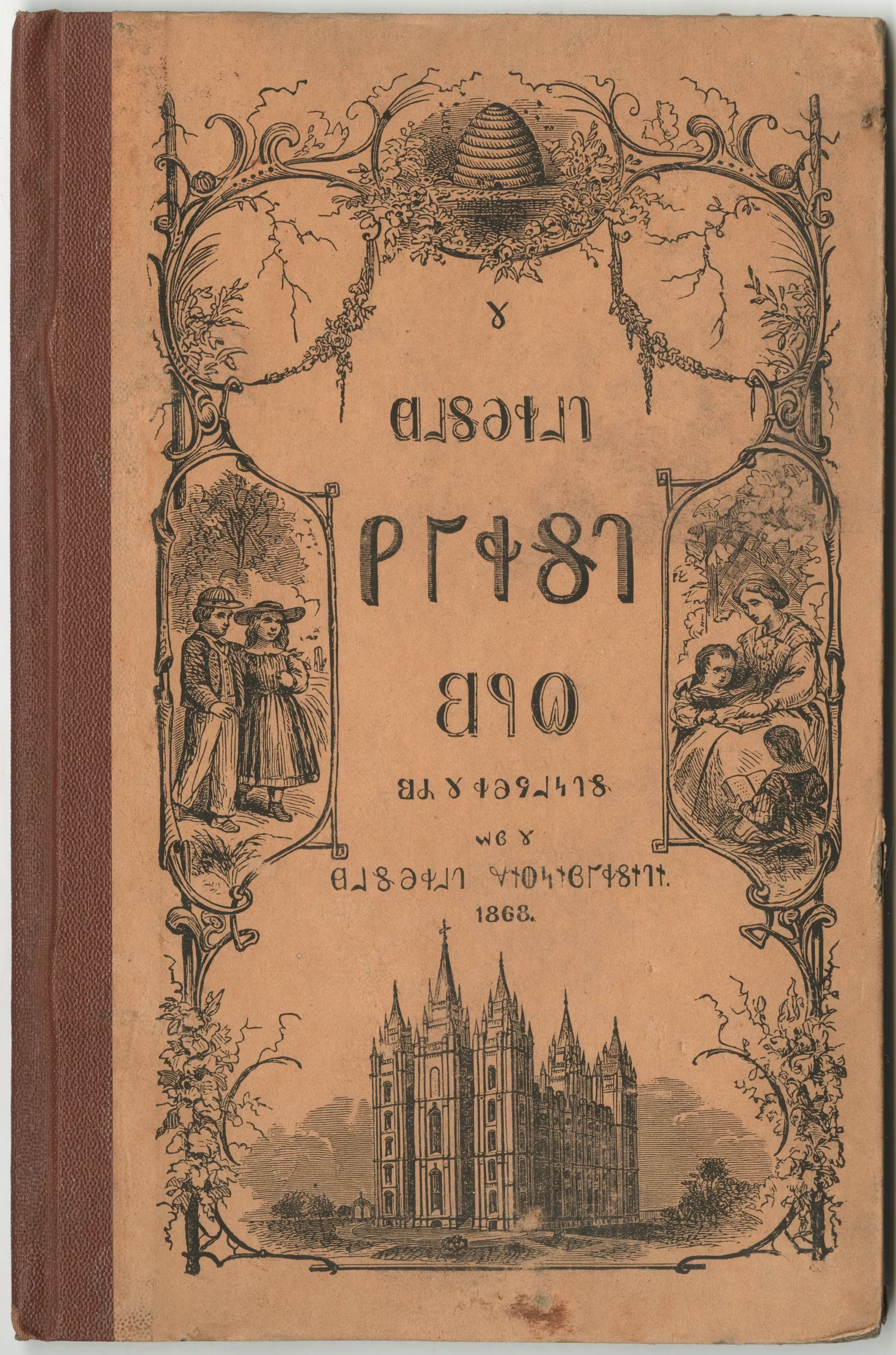

In 1868, a total of 10,000 copies of each of the two primers were printed by Russell Bros. in New York and sent to Salt Lake City to sell for between 15 and 20 cents each. A first edition copy of the second primer is on display at the Utah Christian Research Center.

Young told a general conference audience that October, “We have now many thousands of small books, called the first and second readers, adapted to school purposes, on the way to this city. As soon as they arrive we shall distribute them throughout the Territory. . .. The advantages of this alphabet will soon be realized, especially by foreigners. Brethren who come here knowing nothing of English language will find its acquisition greatly facilitated by means of this alphabet, by which all the sounds of the language can be represented and expressed with the greatest ease” (Journal of Discourses 12:298. Ellipsis mine).

Unfortunately, there were multiple errors in these editions and a correction sheet was distributed. The next year, Apostle Orson Pratt transliterated the Book of Mormon with the Deseret Alphabet and printed 8,000 copies of the first portion, which sold for 75 cents each. The second portion was never printed while only 500 copies of the complete Book of Mormon were created and sold for $4 a copy, a princely sum in those days.

Still, the Deseret Alphabet never caught on with most Latter-day Saints who lived in the Utah Territory. Plans to print other already-transcribed scriptures (the Bible and the Doctrine and Covenants) were skuttled. By 1870, the alphabet system was largely abandoned.

In the 1950s, several boxes containing the primers were found and then sold by the church for 50 cents apiece. This could be why a copy of a primer can be purchased on eBay today for less than $300 each, not a bad price for a book with such a history as this.

After Young died in 1877, the alphabet went into hibernation despite the high cost ($20,000) that had been spent to produce it. However, in recent years, there has been a resurgence of the alphabet’s use. There is even a catalog of literature using the alphabet that features classic works such as Alice in Wonderland, Pride and Prejudice, and the Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

A few years ago, two University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers created the Illinois Deseret Consortium to provide resources to study the alphabet and do digital typesetting. Referring to the time the church spent in Nauvoo in the 1830s and 1840s, its website reads in part, “At the Illinois Deseret Consortium, we are proud to acknowledge that the seeds of the Deseret Alphabet were planted in western Illinois.”

In addition, some instructors of 7th graders in the Utah public school system teach the alphabet as part of the required Utah Social Studies unit. The system even continues today through the enunciation abilities of long-time Utah families. This is because the words in the Deseret Alphabet are not always pronounced the same as they are in English.

For instance, “Deseret” (which is pronounced today as “deh-ze-ret”) is spelled out to be pronounced “deh-see-ret.” Other words are pronounced harse (horse), farbid (forbid), shart (short), fark (fork), and barn (born).

Some speculate that this may be the reason why some extended families who have resided in Utah for years still pronounce words such as these differently, as they learned the unique dialect from grandparents and other ancestors.

Reasons for the Alphabet’s failure

In his article titled “The Deseret Alphabet Experiment,” Richard G. Moore from the Orem Utah Institute of Religion wrote,

“Brigham Young may have believed that conditions were right for the success of alphabet reform. Latter-day Saints were isolated from the rest of the nation during their early years in the Great Basin, making the creation and adoption of a new alphabet more feasible. . . . for whatever reason, though encouraged and promoted by some Church and educational leaders, the Deseret Alphabet generated little interest among most teachers and students” (The Religious Educator, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2006, p. 70. Ellipsis mine).

One reason the Deseret Alphabet failed is that those who already knew English did not see a need to learn a new system. Most of the 19th century schools in Utah were privately operated since public education did not become popular until 1890 when the Free School Act was passed. Many teachers apparently were not motivated to teach this alphabet to their students.

As far as the mindset of the immigrants, imagine that you had just come to Utah from a non-English speaking country and were told that this “code” (the Deseret Alphabet) would benefit you. Let’s say you studied hard and learned it. Since many native English speakers weren’t regularly using this system, how would you ever be able to read and write in English to help you assimilate into society? Learning English with the Latin characters in the first place would have been the better solution!

Brigham Young is known for having taught false doctrine. He also advocated a system to learn English that was doomed to failure. If he really were a true prophet of God, shouldn’t he have done better?

See another article on this topic here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.